Project 722TMX

1

At least five languages are spoken on the refugee camp, yet no one appears capable of navigating the situation here. There is no discourse for articulating this kind of liminality. What we thought we knew of exile, displacement and isolation are made pale and minute beside the concrete walls and barbed wire fences that make palpable the boundary of 722TMX. While words skewed the page, I took to sketching (awfully) my first impressions of the camp, as well as a series of interactions with those contained within it. The first sketch came before our introductory writing class. It outlines the six bodies who sat around the container we had been invited inside for Arabic tea. The containers are much better than the tents, our translator explains. Ah, much cooler in summer? I ask. And much, much warmer in winter! I am told. It is difficult to imagine winter on a day exceeding 40 degrees.

In the single room sit a couple who fled Syria with their children, our translator (another Syrian refugee) who would be leaving on Monday to take up a scholarship to study law in Liverpool, as well me, A and T, tucked away into one corner of the small space. The woman who had made the tea approached me holding a blanket, encouraging I drape it over my bare legs. The translator shrugged, smiled and said something about culture and modesty, y’know, but he hadn’t noted my discomfort, my fidgeting and pulling at the material of the dress over my legs in the way that the women had. Our host smiled and giggled and nodded to me and A, and I mirrored each of these acts as she offered over the blanket I took gladly. Something was exchanged here in the absence of voice, and this kind of gesture would go on to happen over and again throughout the writing session later in the evening. The kind of emotional reality that translates between us without the need for linguistic maps: a language of nodding, hands placed on chests, the passing of smiles and catching of eyes trying to find sense; as well as the heavy shoulders of in-discriminatory loss, and the flushes of shame familiar to each of us.

I have been reading, Neils Lyhne in the time we have had away from the camp. Unlike the literature I’m currently working with, Comma Press’ short-story anthology, Refugee Tales, and Kate Clanchy’s, Antigona and Me, I brought this along believing that the 19th century novel was so far removed from today that I could be distracted for long enough amid Victorian ruffles and frills to take light relief from the camp. I ought to have read the blurb. (Danish) Jacobson’s narrative captures our daily battles between the real and the romantic, hope and reason, the grey spaces that illuminate the silent levels of humanity detectable even on the camp, the wordless exchanges between peoples as they hopelessly attempt to understand themselves and others, to negotiate their shared world and locate their place within it. The novel acutely, at times painfully, exposes the impossibility of completely escaping oneself, one’s lens, as well as the embarrassment of catching yourself in more pleasurable moments, having let thoughts of the brutalities of reality pass away and be replaced by sweeter things. It captures the weight of our connections, agency and responsibility beyond supposed spatial-temporal boundaries; the ultimately inescapable

…silence in thoughts, in words, in eyes, in everything, so that you perpetually hear yourself with the same inescapable certitude with which you hear the ticking of a clock on a sleepless night.

In the past weeks, we have traipsed parts of Mount Olympus, swam in the Mediterranean, and I have caught myself, at times, forgetting why I am here, in awe of my surroundings or occupied by evenings spent laughing over Grecian food and homemade wine. But it is never long before the unsavoury reality re-enters the scene, and the plight of those bound to the camp penetrates someone’s thoughts; conversation falls back to 722TMX and tastes soon bitter.

2

The local beach is made up of shingle, but the rocks in the pools on the mountain are larger, rougher, more distinguished and unique. The process that makes the rocks smooth over time, that sees their edges and inimitable contours whittled down to the featureless, tangible pieces of stone they become is known as tumbling; it can also be achieved using man-made tools and machines. The latter process intends to make something aesthetically pleasing, practical, or both, to shave down the edges of a rock so that it can make up a counter top in a kitchen that won’t cut us as we brush past it to put the kettle on, something smooth enough for our palms to rest upon, unnoticed. On the mountain, I studied a large piece of the jagged rock, the way I had collected pieces of shingle on the beach earlier in the week. Sometimes the process, the ironing out of those contours, is natural; over time edges loosen, become smooth, the potential to slice skin recedes, similarities become more evident than differences. Sometimes we take this rock from the mountain into our workshops. We carve it into the shape we have already foreseen it will become, the shape we wish to see, a shape that is practical for our use. I wonder if a similar process is happening through our writing classes. I wonder whether we are missing what makes a person and their ‘story’ unique, their nuances and quirks, as we attempt to sew together a digestible and non-threatening piece of narrative from the chaos that is today’s refugee ‘crisis’. Indeed, we might pick out certain elements to emphasise the horror, to reveal just how harrowing these people’s lives have been. I understand that there might be value to this.

However, to dramatise trauma in the hope of invoking empathy, without at least gesturing towards the layers of a person’s life beyond their trauma, bypasses the fact that these people are refugees by circumstance and not identity. This discourse reduces those contained within the camp to spectacles which we might pity, wish to help, but the spectator/spectacle dialectic which this kind of empathy hinges upon perpetuates the inequalities between “us” and “them”. The rhetoric which ensues bolsters the victim status of the refugee, strips her of her agency and undermines her subjective perspective, offering instead, a familiar narrative that can be mapped and indeed, colonised.

If we can control the narrative of the refugee ‘experience’, not only do we influence its consumption and absorption into the public realm, but we can affirm, or better excuse our role as agents in another’s suffering. ‘Refugeeness’, to borrow Liisa Malkki term, is performative. Come and tell us your trauma and we will package it nicely enough to attract the right buyers. Is this part and parcel of the market economy of trauma narratives that is detectable in postcolonial literature, too? For Kojin Karatani, the West’s problematic response to trauma and crisis is representative of Western thought more generally. What is crucial to Western thought, Karatani argues, is

…the will to architect that is renewed with every crisis- a will to architect that is nothing but an irrational choice to establish order and structure within a chaotic and manifold becoming.

Karataini’s remarks might begin to shed some light on how the trauma narrative is commodified. A process that has allowed, as Nando Sigona understands, for “Western ‘experts’ and support organisations [to become] the only [valid] voice to speak for refugees […] turning refugees lives into ‘a site where Western ways of knowing are reproduced”. The refugee ‘voice’ is made market worthy.

As Robert MacFarlane points out in, ‘The Gift of Reading’ (a tiny but profound book, whose proceeds go to the Migrant Offshore Aid Station- go buy it…), there are

…two kinds of ‘property’: the commodity and the gift. The commodity is acquired and then hoarded, or resold. But the gift keeps moving, given onwards in a new form. Whereas the commodity circulates according to the market economy (in which relations are largely impersonal and conducted with the aim of profiting the self), the gift economy (in which relations are largely personal and conducted with the aim of profiting the other).

What if, then, what was a supposed act of Humanitarian ‘altruism’, the kind of ‘gift’ that is supposed to profit the other, actually, plays its part in perpetuating the inequalities of globalisation: a process “built not on difference, but inequality.” While, for Gillian Whitlock, humanitarian storytelling harnesses the power to create a platform for spectators to engage empathetically with narratives of suffering and crisis, she is forced to consider whether in fact

“…the transcultural networks of rights discourse and traumatised subjects they empower [are] connected in a competitive economy of affect where violent and traumatised narratives of suffering and loss accrue different value, currency and exchange?”

Perhaps what we tend to think of as the ‘gift’ of humanitarian intervention is often so caught up in the market economy of suffering, that it dispenses the subjective and personal narrative in place of something “more dramatic” and in turn, more saleable. Perhaps it’s a catch-22. Indeed, it is important that these stories are disseminated, but to do so, our job here, it appears, becomes one of instruction: to frame someone else’s trauma and package it ready for the shelves. To target an audience’s cathartic tendencies.

For Richard Schechner, many such acts of intervention operate with an “underlying goal[ …] to bring all subsystems into harmony and under control.” We play the “game of globalisation”, a process in which the “players must make sure there is no actual “level playing field”. A person’s narrative, and in turn their identity, must be architected in such a way that can be looked upon but never lived within: for a singular refugee ‘voice’ or experience does not and cannot exist. The project I am involved in wants refugees to tell their stories. Does this mean their story as a refugee? A story from before they were forced to flee their homes? Are we looking for an ‘authentic’ refugee voice, and what form can this take? Can there ever be such a thing? The lack of clarity is troubling. While our power resides our stories and, more still, our ability to tell them, I cannot help but worry about the effects of this space, or better non-space(?), on a person’s ability to write, to speak, even to think of a story that is not bound to a place that strips away their narrative and in turn, their power. I fret over our entering of this space with the intention of getting something out of it. Yes, perhaps there is benefits to be discovered through the project, but these people believe we are here to help them more practically that we can. Hence, while I understand that changing the narrative of crisis is essential during these times, what do we change the narrative to if we have come here to instruct people what to write? Whose power is affirmed here?

Rebecca Solnit understands that while “Changing the story isn’t enough in itself, it has often been foundational to real change […] every conflict is in part a battle over the story we tell, or who tells and who is heard.” I see that both sides of my argument if I can call it that, are flawed. And I think what Solnit remarks here in some way captures one of the problems. It is true that the story must be changed, and perhaps we can help with that, but the battle over who has the power to tell stories, realistically, remains unchanged. Even sitting here now, I am telling and being heard from a privileged position. For Solnit, our stories are,

…[our] compasses and architecture; we build our sanctuaries and our prisons out of them, and to be without a story is to be lost in the vastness of a world that spreads in all directions like arctic tundra or sea ice.

By acting with the intention of ‘exposing’ the ‘authentic’ refugee experience, might we be building prisons where we intend to build sanctuaries, creating and cementing an identity from a situation, from the narrative of a place; are we perpetuating a myth that itself becomes a destination, rooted in a location that is neither here nor there? I wonder what other stories confined to times and locations beyond this condition exist. On being asked to provide a description of the camp, one young and eager woman wrote a poem in the form of ancient Arabic that our translator did not wish to read, despite encouragement; it didn’t fit the narrative. She didn’t come to another session. If, then, as Solnit believes, “a place is a story, and stories are geography”, should we not instead be asking what happens to those without a way to navigate their new surroundings, without a way to assert their identity within their new and alien space? For this is a space that seems to elude all meaning; it is a space that strips away a person’s identity to replace it with another homogenous term, one that carries where it goes a plethora of negative connotations: the passive victim of humanitarian intervention versus the threat to the fabric of Western identity. Does this project perpetuate this simplistic polarity? Or, does it have the potential to establish new meaning: to be a site of subversion in what might be considered a heterotopic space? Perhaps we will gain a better understanding of the role of the storyteller and her relationship with her platform as the project progresses. Perhaps there will be stories to read in the end, or maybe the classes will have, at least, provided a moment’s respite from the camp. What I have learned is that changing the narrative isn’t quite as easy as I had once ignorantly believed it might be.

3

The next sketch I have is of a woman who attended the first session. She is noticeably older than everyone else. I was surprised by her eagerness. She, like the other women, turned up later. We were told the women are dealing with the children, putting them to bed, the way that mothers all over the world do. The translator refers to her as elderly, and although she is certainly much older than anyone present, I don’t think elderly does her justice. She might be seventy, perhaps more, it is difficult to discern a person’s age here. She was tough, her hands and her skin were hard, but her smile was as long as it was soft. I caught myself nostalgic for another time and place. I continue to catch myself in this space throughout the first session. The woman made me think of my dad’s mother: the single matriarch who raised nine children and several grandchildren (including my dad), who was partial to a bottle of vodka and long naps in the sun, but never missed one of my dad’s football matches and cooked a roast dinner for all of her family each Sunday without fail. This was the first time I realised that it is impossible not to supplant ourselves in one way or another into these peoples’ lives, and question whether this should bring me unease or content. At the next class, a Greek school teacher who has come from Alexandreia to attend the class read out her homework. She gave a description of one member of the camp. She reminds me of my grandmother, she says, she is strong and brave, but she has kind eyes and a deep smile. Like my grandmother, I imagine she has raised many children, and perhaps even some grandchildren, and that she is loved and highly respected. None of the Syrian women attended this session, but the men are quiet, smiling and nodding; I thought of my dad.

The following class was more difficult. The ten or so women who had turned up eager and excited on the first day did not show. The room was semi-filled with older, tired looking men. An elderly man came into the make-shift classroom around half way through the session along with a child who was noticeably disabled. He held her hand and walked with his remaining hand clutched around a walking stick to the front of the classroom where he took a seat in what had been A’s chair. The child sat beside him and cuddled in. The man rested his head atop the child’s the way you do in the back of a car to make sure their necks don’t become stiff, taking comfort in the smell of their hair and the warmth of their skin: their neediness and vulnerability. I presumed the child was his grandson, whose age I’d have put around nine, like my brother, but we would later be told it was his daughter; she is twelve. He remained in A’s chair at the head of the classroom and furiously wrote down two pages before handing it to the translator. The translator refused to read the story. He said that it had things to do with his daughter in and it would be too harrowing. The man left the room irritated and anguished. I followed him into the hallway, but it was impossible to speak with him given our mutual lack of the other’s language. Another man explained to me in broken English that his daughter was tortured, left behind in Palestine. When I looked at the man, he put his hand to his chest, and nodded with his head down, before calling the child to leave with him. I didn’t realise how much hearing this had affected me until my mother called me later on. If you are not smiling in the camp, if you do not make yourself numb you will break down. However, re-entering a space again where it is okay to be weak and soft, the reality that has made home in your stomach rises to your throat and refuses to shift until it is released. I cannot imagine how it must feel to carry this weight around in your stomach indefinitely.

We eventually had the elderly man’s story translated. L’s mother is Moroccan and was able to explain the main elements of the narrative. The child, whom we had thought was a little boy, was a girl, his daughter. She is badly disabled and needs round the clock care. He cannot get a job because he has no papers, and even if he could, with his ill health and being the only carer for his daughter mean that working would not be possible. He had a son, too. He explains that he gave his son, aged fourteen, to friends in Denmark so that he could have a better life. L’s mother says his friendship with these people is ambiguous, he uses the term lightly, that it seems as though he did not know them before. He explains he is shunned in the camp because people think that he sold his son, but that this is not true. He says he is glad for making the difficult decision because he believes his son will have a better life there. I wonder whether the interpreter did not want to read this story because he was saddened by the man’s situation, or because he too was critical of his decision to ‘give-up’ his son. The men’s responsibility for the safety and well-being of their families has cropped up regularly in our conversations. One man explained how helpless he felt on the boat to Greece, what kind of man was he, he asked, if he could not protect his children. Another man explained how he pastes a smile on his face for the sake of his children, who should have no idea of his pain.

At the next session, the older man returned. He looked different to the first sketch I’d made. He did not sit at the front of the classroom but pulled a chair out for both him and his daughter. Another man in the class was making his frustration known. He shouted in Arabic, confused about why were there, how we were going to ‘help’. Through translation, L attempted to explain what the project was about, but the man, and now other men too (for it was a room of only men this time) became irritated. Some left. Moments before the elderly man stood to speak again, his daughter had reached for his face, and he had leant in and kissed her and smiled and she had laughed audibly. I was pleased he had returned, eager to let him know we had managed to get his story translated. However, on rising from his chair, he took to the centre of the room and began to shout to L. The new, young translator, who would, after this session leave the camp because he was too depressed to remain, attempted to keep up with the man’s speech. He says that he cannot leave, that he is trapped here, the translator explained. He pulled his daughter from her chair in frustration; she didn’t appear perturbed. She is very badly disabled, he said. Pulling her pants down partially he pinched her nappy with one hand and pointed to it with his other. Look, he said, she needs round-the-clock care. How can you help us? If I had two thousand euros I could take her and get her the care she needs, he said. What can you do to help us? He took the child’s hand and left. We haven’t seen him at another session since.

4

The day after Eid, celebrations were thrown in the camp. Children occupied the stage with what appeared an endless supply of balloons and danced to a mix of Arabic music and European pop. Two girls, who can’t have been much older than eight, danced like they were on MTV, each one trying to outdo the other, leaving some, I sensed, a little lost for where to look… These light-hearted activities, however, were punctuated by a performance which took us all off off-guard. Some of the older boys joined the stage, while the very young children were removed. What looked to be a thin mattress was draped in blankets and pulled centre stage; the children who remained gathered around it. Along with the introduction of a moving piece of Arab music, the narrator, an older man, began to speak through a microphone.

Sounds of crashing water soon accompanied the narrative, and it became clear that the children were performing a voyage across water, a journey many of them will have made to get to Greece, a journey in which many others will have made without reaching land again. The children re-enacted scenes of people falling from boats, giving the kiss of life to little actors who lay limp in the imaginary waters. Soon, three small girls, perhaps aged between six and eight, joined the stage dressed as angles. They circled the stage around the limp bodies, moving their arms up and down softly; two were unmoved by the play, but one was notably sobbing. Eventually, those who had ‘died’ were picked up by the older boys, many of who were also crying, and carried off-stage. The music eventually stopped, as did the movement of the small girls, and a moved audience clapped the performance. I look around to check the faces of the other Syrians. Some of the women were crying, but none looked as awkward or uncomfortable as I felt to be stood there, watching on as their children acted out their history. To borrow T’s words, it was all a little too much. This was their performance, their history, that is what those kids chose to show us. I’m still wrapping my head around that, but my stomach tightens at the thought.

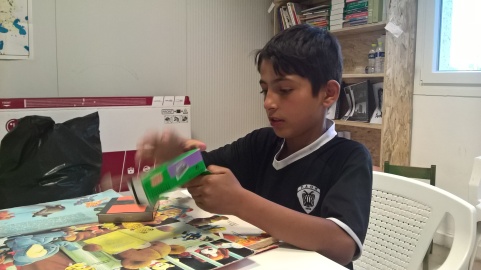

Yesterday I took a break from the classroom. I had thought in the morning about coming home the same day, looked for flights and trains. I have made my concerns about the project known, that I worry our presence on the camp might be having a detrimental effect. However, I found out that the women in the camp have said they would feel comfortable speaking with me alone on Monday, so I plan to be present for that. There is a heatwave in Greece at the moment; it reaches 40 plus on the camp and people had retreated to their containers for a siesta. I rested my arms over by knees and leant my head down to meet them. Are you OK? Are you sad? Or sick? I raise my head to see a little boy I met a few days ago running towards me. He’d been tormenting me with balloons, chased me around and been intrigued by my backpack a few days earlier. I explained to him I was fine and just taking a rest, and began asking him about his day. He continued to ask why I was sad, whether I missed my home or my husband. I explained I was fine, and that I was husband-less. He was keen to know why I don’t have a husband because I am quite old now (thanks, kid). We chatted about football, about his family, about my family. I showed him photographs of my dog and brother who is the same age. He liked Jamie’s Liverpool kit and thought the dog was so cool!

I’m going on a helicopter next week, he said. I have been on a helicopter before. He made the sounds of the propellers with his tongue, and I tried and failed which he found highly amusing and asked me to do it again, and again, and again. He told me he was going to live in Germany with all of his family in one week. He is excited, he says, because in Germany kids have bicycles… and remote-control cars… and go to fun schools… and can watch football games. His favourite team is ‘Christiano Ronaldo’. He’s a gorgeous kid, confident and sweet. I take his photograph, and he gives me a big grin and asks if we can take one together. He warns me of the snakes on camp (I haven’t seen one yet…), apparently, they’re everywhere! Everywhere! He re-enacts what happened that very morning. At the back of my container, he points it out, there was a snake from here to here. He walks from one side of the stairs to the other, drawing out a snake worthy of a place in the Guinness World Record book. A coach arrives, and he leaves because his family is on it, he says. I hadn’t noticed the coach pull up. We say our goodbyes, and I return to the classroom.

A little later, B, an Army officer who continues to help out at the camp despite their presence having been deemed ‘no longer necessary’, explains that the bus is taking people to Athens, half a day’s drive from Alexandreia. Most of them won’t have the right documents and will be back here this time tomorrow, he says. They go to Athens in an attempt to have their asylum claims processed so that they might finally move on from Alexandreia, potentially from Greece. I hope the boy’s family have their papers- that his idea of Germany next week wasn’t like his tale of the gigantic snake. In the car on the way back to Litochoro that evening, T will tell me that, last year, another army officer explained to him that at the current rate of UNHCR pre-registration, it would take 35 years to process all the refugees in Greece. He believes this process has speeded up since, however, the new EU regulations (i.e. the March 2016 EU-Turkey deal) mean that some refugees have become trapped in Greece, unable to move on, only able to go back to Turkey or home (to Syria). I wonder where that kid will be in ten, twenty, thirty years from now. Again, it’s difficult to find words for the hopelessness and the loss here.

B explains that the people who are left here, are those who have already been knocked back countless times. They’re the ones without skills or who have difficult cases. I look around and see a mother carting her three children across the exposed tarmac square, a group of young men chatting in the shade and a queue of people hot and impatient, waiting to board the bus that will likely bring them back tomorrow. They organisations are leaving, B explains, because they believe the camp can now run itself, but this is clearly not true. The camp worked because of those organisations. This week, a communal kitchen where people come of an evening to cook will be closed for good. The organisations must go to camps that are in much worse conditions. I can’t bring myself to think about that as B is talking. Worse than this? Is this really the best we can do? Perhaps we ought to aim for somewhere in-between meeting someone’s biological needs (which is obviously necessary), and sending in a group of creative writers for storytime. One man’s words stick. When we arrived they sent in doctors, he remarked jovially, but what we really needed were therapists!

I return once again to the classroom, and my new friend follows me in. We find a book, and he reads it to me in Greek. Witnessing the innocence and resilience of a child is a light relief from the sounds of a grown man crying in the next room.

Lovely written

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve just read this sitting in a coffee shop in Bristol. I feel a million miles from where you are and yet the familiarity and beauty of the human condition is laid out so honestly, and there is nothing but respect to be found here. Look forward to seeing where you take this blog, mate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment; it has made my morning. All the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading this from London and I feel I am right there. Both blogs from your writers this morning have made me think. I agree with the previous post – this simple human connection must mean something, and I can only pray that we do more. It is ironic and sad to think that at the same time there are articles about declining populations in Europe, we cannot just open and assimilate those who have so much to offer – the whole future. I think about my grandparents’ mountain village in Greece, now depopulated, only coming alive for a few holidays, and how once those same ancestors came from elsewhere, too. A wonderful piece I saw on a Syrian who married a Greek twenty years ago and became the mayor of a depopulated village, and opened it up to refugees, who have reinvigorated the economy and brought life and young people back. England has rejected immigrants and is now barrelling down a tunnel of darkness with no end in sight. Those who had the strength and courage to leave are the ones who will make the future, as they did in America when my grandparents and great grandparents arrived.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for you comment; its given me much to think about. What is the name of the village? I am keen to know more. And, you’re very right, we could do so much more.

LikeLike

My grandfather came from “Megalovriso” and my grandmother from “Metaxaxori” which was lower down the same mountain – Kysavos (the villages were also called Nivolyani and Retsina I think). They met in New York. When I went there in the 1980’s it was still a thriving village full of farmers and shepherds, but when I went back recently it had been cleaned up considerably – no chickens, no donkeys, no people. The streets and houses looked so clean but it was empty – like a ghost town. I guess many moved to the cities – like Larissa, and go back for holidays or have sold as holiday homes. That’s not all bad, but there is plenty of room – not just in Greece but in many rural places in Europe which are going back to wilderness because the younger generation does not want to stick around to work the land – and I can’t blame them! But to keep people penned up the way we do – in the UK as well where I’ve been hearing about indefinite detention and the way we keep Asylum seekers from working even if they are “let out” into the community just speaks to such an emptiness in our collective imagination. Yet I am convinced the majority do not feel this way, only a vocal, powerful minority. Sorry for the long response!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No need to apologise- all very interesting stuff. And, I completely agree. Detention centres are another level of horror. Have you read Refugee Tales? It is a short story anthology from Comma Press. Creative writers work alongside asylum seekers and those who are or have been detained, to tell their stories. I’d highly recommend it.

LikeLike

Link to the project: http://refugeetales.org/

LikeLike

what a touching post

LikeLiked by 1 person